Within the Mediterranean region, Syria has been a key strategic battleground for regional and external powers. Due to a civil war that began in 2011, Syria has become internally fragmented. The conflict has tragically resulted in the deaths of over 600,000 and the displacement of an estimated 13 million. However, in late 2024, the situation in the country suddenly changed, as the civil war ended. The dictatorship of Bashar al-Assad collapsed in December and since then a new political authority has emerged, shaking up the previous status quo. Amid this turbulence, longstanding allies of Assad — like Iran — are seeing their influence diminished while new powers — especially Turkey — are moving in to maximize their influence.

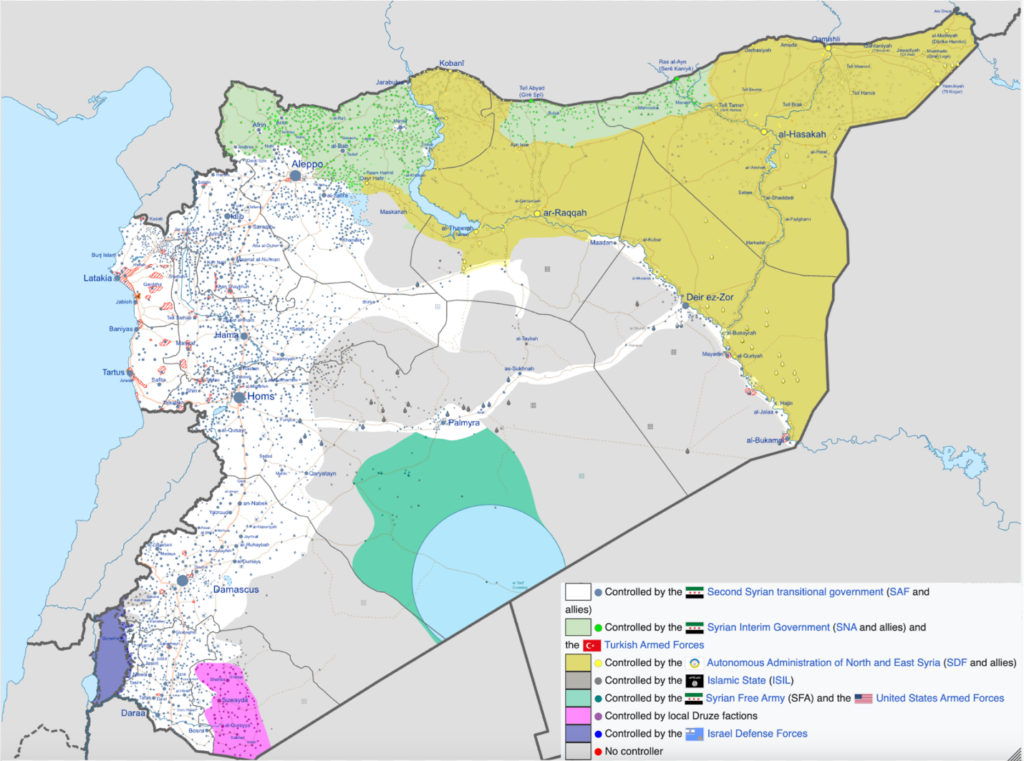

In 2011, during the height of the Arab Spring, Syrian protesters sought to remove the Assad regime — that had ruled the country with an iron fist for more than five decades. Bashar al-Assad — who in the year 2000 had taken over the presidency after the death of his father, Hafez — was a controversial authoritarian leader who attempted to brutally silence the critics to maintain his power. By September, the protests evolved into a violent militant rebellion which ignited the Syrian civil war. Over time, the rise of internal opposition as well as the involvement of external actors led to the fragmentation of Syria within its borders. By 2023, rebel groups mainly occupied the northern areas of Syria, with some being aided by Turkey. In the north-east, Kurdish forces established a de facto autonomous government and were soon involved in the fight against the self-proclaimed Islamic State (also known as ISIS or ISIL) as well as in clashes with other Syrian groups backed by Turkish armed forces.

For more than a decade after the outbreak of the Arab uprisings, Assad’s regime remained the de jure government of Syria. Assad received arms and support from Iran and Hezbollah (a Shia-Islamic organization in Lebanon). The Syrian regime launched violent offensives against his own people, including the use of chemical weapons, to crush the rebels and maintain his authority. Over time, however, Assad’s grip started to weaken, and by 2024 the Syrian opposition, led by a rebel organization known as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), managed to mount a successful offensive that led to the overthrow of the regime. A jihadi militia, HTS was originally founded in affiliation with al-Qaeda and by the time it defeated Assad, it was labeled as a terrorist organization by many states, including the U.S. and Turkey. Recently, however, the American administration led by Donald Trump has shown a willingness to recognize the new Syrian government and work with former rebel leaders.

In late 2024, HTS was able to topple the Assad regime in twelve days: on November 27th, the rebel group launched its offensive and captured Aleppo in three days. This was a strategic victory for the HTS, given that Aleppo is one of the major cities within Syria and was a strong center for Assad’s forces in the north. Building off the momentum of the victory, HTS quickly mobilized and headed southwest capturing the cities of Hama, Daraa, and Homs. This created a path for the rebels to quickly mobilize to the capital and on December 8th, Damascus was captured. HTS established a caretaker government (which was replaced on March 2025 by a new transitional government), Ahmed al-Sharaa — the HTS leader known by the nom de guerre of Abu Mohammad al-Jolani — became president and Assad fled to Russia. With the establishment of a new domestic political authority, Syria also started to reshape its relations with regional powers. Iran’s presence in the country, which was a major factor under the Assad regime, has been strongly reduced, while Turkey is expanding and consolidating its influence on the country.

Iran: A Decayed Axis

Iran is a controversial actor in the region. Some Iranian initiatives can be interpreted as a power grab in the Middle East rooted in a radical ideology. On the other hand, the actions of the Tehran regime can also be seen as a defensive response to a hostile environment. Iran has sought to create what it called an “Axis of Resistance” with many governments and non-state actors in the Middle East to boost its security and ambitions throughout the region. Assad was a major pillar of the “Axis” but after his fall, the Iranian network was limited to non-state actors. The members of the “Axis of Resistance” currently range from Hamas in the Palestinian territories, Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Houthis in Yemen, and other Islamist-leaning armed forces located within Syria and Iraq. These actors are financed and receive specific security guarantees from Iran, but they retain their autonomy and pursue their own agendas, rather than being fully controlled by the Islamic republic.

As long as Assad was in power, the Tehran and Damascus regimes were close allies, providing each other not only security but also economic benefits. Syria was particularly important due to its strategic geographical location, as Iran has no direct connection to the Levant. Thus, Syria and Iraq provide a route to the Mediterranean. As the Assad regime began to crumble, the Iranian infiltrations in the Syrian state started to unravel. With the additional weakening of Hezbollah, Iran’s leverage and power balance have begun to falter.

Iran financially contributed to support Bashar al-Assad. It was reported that during the course of the civil war, Iran invested between $30 and $50 billion to ensure the survival of his regime. Additionally, as indicated by Reuters, uncovered documents show Iran’s neo-imperial ambitions in Syria, aiming to make the country economically dependent on Tehran. The documents describe plans to invest billions of dollars into Syria’s post-civil war reconstructions as a means to consolidate Iranian influence in the country — a sort of Iranian “Marshall Plan” for Assad. With the collapse of the regime and al-Sharaa’s disassociation with Iran, these plans are now terminated. Al-Sharaa must now find other benefactors to help finance the redevelopment of Syria; thus, this is where Turkey comes into play.

Due to the decay in the “Axis” and having no standing to intervene against HTS, Iran decided to not interfere with Assad’s fall. What proved to be an additional factor to this decision was Assad’s diminishing usefulness to Tehran: as some opinions suggest, Assad began charting his own ambitions that clashed with Iran’s regional interests. The weakening of the “Axis” members and the diminished influence of Iran within the region allows for the emergence of other actors. In the case of Syria, Turkey seems to be rising as the new would-be “mentor” of al-Sharaa’s government.

Turkey: A Transactional Influence

Turkey is a crucial geopolitical actor in the eastern Mediterranean. Bordering states in Europe, Eurasia, and the Levant, it serves as a geographical bridge across many regions. Today, Turkey remains a key NATO member and a strategic partner of the European Union. However, close relations with the West have not stopped Ankara from taking independent initiatives, including engaging with Russia. Ankara and Moscow have engaged in bilateral partnerships for economic gain — with one of the main areas being focused on energy supply. This illustrates the ambitions of the Turkish leaders to establish their country as an independent actor. Turkey seeks agreements that will ultimately bolster its economy, security, and overall prosperity as a means to strengthen the regime created by Recep Tayyip Erdogan – who has dominated Turkish politics since the early 2000s — and maximize the country’s geopolitical influence.

Turkey’s quest for influence and power can put the country at odds with other actors in the Middle East and North Africa. Though they share specific yet limited security and economic concerns, Turkey and Iran maintain a historic rivalry. Syria has been a major battleground for this rivalry. Turkey was a strong advocate and supporter of the oppositional forces to Syria’s former President Bashar al-Assad. As stated previously, with the fall of the Assad regime, Iran lost all strategic cooperation with Syria. Turkey, on the other hand, has been able to capitalize on the situation and has worked closely with Syria’s new leadership to shape the future of the state.

Though Turkey and the new Syrian government appear to be in good standings, the Turkish government’s national interests may strain the future relationship of the two states. Historically, Turkey sees Kurdish ambitions for autonomy as a threat. The Kurds are an ethnic and linguistic population spread mainly throughout Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. Turkey has considered the Kurds as a top security threat, with a major insurgent faction being the Kurdistan Workers Party (referred to as the PKK) — which is classified as a terrorist organization by Turkey and many other states. Recently, the PKK seems to have abandoned the armed struggle and struck a peace agreement with Turkey. However, the Kurdish question still creates complications for Ankara’s and Damascus’ relationship as north-east Syria is occupied by Syrian-Kurdish forces known as the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), led by the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) and thus considered by Turkey as an extension of the PKK. To combat the SDF, Turkey has occupied an area along the northern Syrian border.

The challenge for Turkey is now to maintain its presence in Syria without undermining the stability of al-Sharaa’s government through excessively intrusive violations of Syrian sovereignty. Recently, al-Sharaa has established Kurdish rights in Syria and introduced a plan to integrate the SDF into the Syrian national military — which Ankara is seemingly on board with. However, the main issue for Ankara in this context is the backing granted by the United States to the SDF. This force has been a crucial ally of the U.S. in the fight against ISIS. With the fall of Assad, Turkish forces and the SDF resumed fighting over contested territory. Currently the U.S. has publicly supported a ceasefire and a “managed transition” with regards to the SDF’s role. However, it is not clear whether the U.S. would be in favor of having the SDF integrate into the Syrian military. Nevertheless, if Turkish forces were to continue to launch attacks on the SDF, this may complicate the relationship between Ankara and Washington, and the U.S. may respond with sanctions or further retaliation.

Conclusion

The end of the Syrian civil war has shaken up the status quo in a critical area of the Mediterranean chessboard. Iran, a long-time backer of the Assad regime, is facing an increasingly hostile environment in Syria and may eventually even pull out of the country. The “Axis of Resistance” has been decaying with the significant weakening of Hezbollah in Lebanon, due to Israel’s offensives. Now with Assad gone, Iran has lost another critical piece in the contest for regional influence. Additionally, uncovered reports showed that Tehran abandoned its efforts to maintain control of Damascus through investments in redevelopment. The current Syrian government has seemingly severed ties with Iran and shifted to working with a new ally, Turkey. The Turkish government has found it in its interest to aid al-Sharaa’s government, and coupled with support from the Trump administration, this can lead to new doors opening for Syria on the global stage. Nevertheless, tension can still be present for Turkey with the situation of the Kurds. As Syria seeks unification within its borders, Turkey must allow for some leniency and not to be clouded by its personal interests. Ultimately, with Turkey acting as a major sponsor, the al-Sharaa government in Syria seems to have a chance to consolidate. However, it is still imperative to maintain a cautious eye as this situation develops further.

Lorenzo Di Franco-Cascone